Hello everyone and Merry Christmas! Hope you all had a great time celebrating with your families and friends.

A few weeks ago the Internet exploded with articles referring to a revolutionary new study in the field of nutritional science. I am referring to the study from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, published in a highly influential scientific journal Cell on Nov 19th[1], which has conclusively proven the need for personalized approach to nutrition. The same research group was responsible for another mind-blowing article on how artificial sweeteners change the gut microbiome just a year ago in Nature [2]. Interestingly enough, the “personalized nutrition” idea turned out to be strong enough to take our minds off bacon for a while (bacon has been pronounced a Group 1 carcinogen, in case you have missed it.)

So what’s all the fuss about?

Our responses to certain foods are shaped by two factors, incredibly important to our overall wellbeing: hormones and gut microbiota. For instance, an excellent paper from 2 years ago linked higher cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in red meat consumers with their gut microbiome composition [3]. Red meat lovers have different gut microbiomes than vegetarians, which makes sense if you consider another recent article that has demonstrated that even transient changes to our diet can significantly alter the gut microbiome [4], depending on which types of foods we preferentially consume (animal products or vegetables). The culprit in the case of CVD induction turned out to be not just red meat, but its component L-carnitine, which is also a prominent component of many supplements marketed to fitness freaks based on its proclaimed “fat-burning” properties.

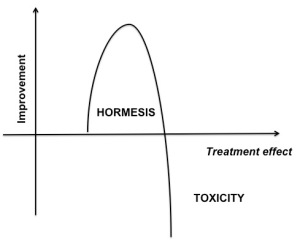

Anyhow, our hormonal responses to food (particularly, insulin secretion), as well as composition and diversity of our gut microbiota [5] both largely affect how we process certain foods and whether or not we gain weight while exposed to a certain food environment. What Israelian scientists have now comprehensively demonstrated, is that blood glucose response (which essentially depends on insulin production) can be very different in different individuals who have eaten precisely the same foods. Seems obvious, right? However, up until now we have been largely taught that certain foods are “bad” for us and promote obesity, while others are “good” and beneficial for weight loss. Turns out, not really. Some people can consume sugar-laden baked goods without as much as an extreme blood sugar rise, while others will develop a strong reaction to plain bread. And it’s not necessarily the evil processed foods that are to blame. One example presented in the article was the response of two study participants to bananas and cookies: while eating a banana had almost no effect on blood sugar in one participant, his/her blood sugar spiked after eating cookies. Kind of what is expected, right? Bananas are naturally sweet, but not as bad as cookies, aren’t they? Well, for another participant they were: while eating cookies did nothing for his/her blood sugar levels, a nutrient-rich banana caused a profound spike of blood sugar levels. Moreover, it seems that having prevalence of certain microbial species in your gut microbiome is positively correlated with blood glucose level control. Not surprisingly, so are certain markers of metabolic syndrome (HbA1c%, for instance). Interestingly, adding more fat to the diet may or may not improve glucose response in some people, so the reaction to fat consumption is also very much individual. The amount of dietary fiber consumed was positively correlated with adequate blood sugar control in the long-term, even though it was, surprisingly, associated with increased glucose response immediately following the meal. The scientists also used a computational approach to design individual “good” and “bad diets” for study participants and monitored their blood sugar levels for a week. Not surprisingly, the “good diet” weeks were characterized by relatively stable blood sugar levels, while “bad diet” weeks featured huge spikes in blood sugar. It was, however, quite striking, how different those “good” and “bad diet” weeks were for individual study participants. Foods classified as “good” for some people were added to the list of “bad foods” of other people and vice versa, including both high-carbohydrate and high-fat foods.

The take home message of this study is relatively straightforward: there can be no universal nutritional recommendations (at least in terms of their effects on blood sugar). One size does not fit all, not only because some people naturally prefer meat to oranges or cookies to bananas. So maybe next time you try to jump on the latest trend bandwagon, don’t be surprised that it doesn’t work as good for you as you have anticipated. While some might thrive on a low-carb diet, others really need their carbs to function. And that’s totally normal, since if your blood glucose level control is in check and your microbiome is great at metabolizing carbs and sugar, it’s much less harmful for you to indulge in Christmas cookies that it is for some other people. Generally, if you know your body well and follow an intuitive eating approach, which is becoming increasingly popular these days (at least in part due to the increasing confusion in the diet camp and the guidelines on that to eat or not to eat rapidly changing), you might have already noticed how you feel in response to certain foods both short-term (if they make you tired or more energized) or long-term (if increased consumption of certain foods causes weight gain or chronic fatigue). Does it mean we should all trust our guts? Not necessarily. Ideally, as this study has taught us, the best way to determine your response to any kind of food is to monitor your blood sugar levels. Even though such tests are minimally invasive, I do not think that they are the best option for most people and are certainly not necessary (unless you are extremely curious and prone to n=1 experiments with your body – to those I say, go for it). Constant blood sugar level monitoring is, however, crucial for those who suffer from diabetes, since the standard diet recommendations might not fit your body’s needs. I guess such tests could also benefit those who already show insulin resistance and are at risk for developing diabetes.

Now, while it is clear that we are not all the same in terms of metabolism and blood glucose responses, the thing with gut microbiome and obesity (or other conditions), in my opinion, is sort of a “the chicken or the egg” story. While there are clear correlations between prevalence of certain gut microbes, as well as general microbiome diversity and obesity (or, as in this case, glucose responses), it is not quite clear what comes first: changes in diet that lead to changes in the gut microbiome and then to obesity (or they both go hand in hand) or do the changes in gut microbiota provoke obesity. This question, I think, does not yet have a clear-cut answer. While antibiotics have been linked to obesity in some studies, other studies have shown beneficial changes following antibiotic treatment since they may also eradicate the “bad bacteria” that contribute to disease. Also, I do believe that long-term dietary habits have a bigger role in shaping the gut microbiome than a single course of antibiotics. Other factors, such as bad dietary habits (lack of fiber, high sugar intake), definitely have a huge impact on the microbiome, however, those effects can be reversed once the diet is changed accordingly. Therefore, I do think that it is our diet that primarily influences the gut microbiota and diet-induced changes can then predispose us to certain conditions. Now, what kind of diet is good for each of us – that seems to be less clear than it used to be. The only advice that seems appropriate is that anyone who is interested in maintaining good health should not necessarily trust the latest dietary recommendations. But do throw in an occasional blood panel for good measure! I mean, preventing disease is always better than treating an already existing condition, and tests are not only for those folks who do not feel well. Our bodies are extremely robust and will tolerate our miserable lifestyles for years but at some point you really should start taking care of yourself.

With that I wish you a very happy, healthy 2016!

References:

- Zeevi et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. In: Cell, 2015

- Suez et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. In: Nature, 2014

- Koeth et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. In: Nature, 2013

- David et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. In: Nature, 2014

- Le Chatelier et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. In: Nature, 2013

(pic from memegenerator.net)

(pic from memegenerator.net)